We’re building a strawbale house! But why?

In case you’ve somehow stumbled upon this article without any context about us – we’re really concerned about climate change and the destructive trajectory modern society is on. The whole point of our complete lifestyle change and move to Tassie is to set ourselves up to live as comfortably as possible in the predicted climate future we’re facing, whilst also not contributing to the problem. Residential buildings are responsible for more than 10% of total carbon emissions in Australia (DCCEEW 2024), so minimising the environmental impact of our project has been a key factor for consideration in all our decisions. No construction project will ever have zero impact on the environment, and we’ve had to make some tough choices when faced with competing priorities.

Choosing straw

We knew as soon as we decided to build a house that it would be made of natural materials – this wasn’t even a discussion, it was just assumed by both of us. We did a lot of research into various natural building methods to determine which would best suit our needs. We did workshops with hempcrete, cob, and light earth. We volunteered on a strawbale house build, and we also volunteered on an earthship build in South Australia. We thought for a while that we would build an earthship, however we eventually landed on strawbale for its unmatched insulative properties.

Straw bales have been used in construction for over a century. They’re low-cost for the thermal performance they offer, and they’re a waste product so their embodied energy is incredibly low. Working with them is labour-intensive, however they’re easy to work with and therefore unskilled people can learn quickly to put straw bale walls up. They sit within a timber frame so the rest of the house is relatively standard, it’s just that our walls are 400mm thick.

Passive solar design

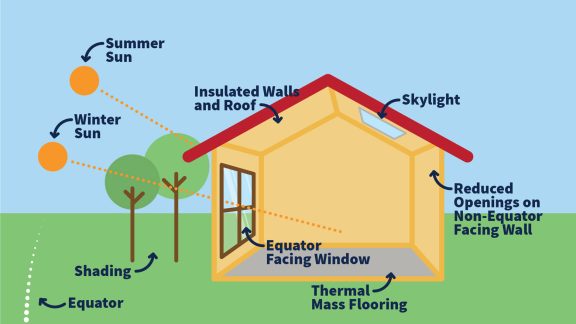

When we were searching for land, our number one requirement was a north-facing aspect to allow for passive solar gain. The sun rises in the east and sets in the west, and in summer it arcs high in the northern sky (in the southern hemisphere) whereas in winter it arcs quite low in the northern sky. This means you can calculate the sun angles for different times of the year and design your house to allow winter sun in while excluding summer sun.

As such, we’ve designed our house to be long and narrow so that every room faces north. The winter sun, which is low in the sky, will come through the windows and heat up the earth floor which will store that heat and radiate it back into the room at night, significantly reducing, and perhaps eliminating, our mechanical heating needs. We’ve also calculated the width of our eaves to exclude the sun from hitting the windows in the hottest months, which will keep the house cool. Orienting your house according to the sun is the easiest and cheapest thing you can do to minimise its required operational energy – provided you’ve factored it in from the beginning with your site selection.

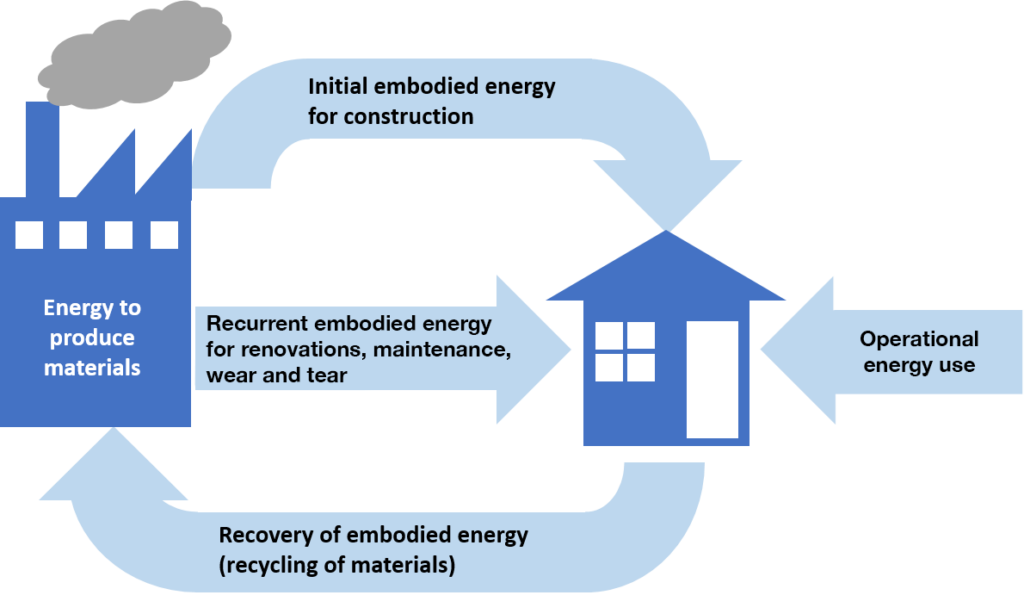

Operational vs embodied energy

There are two main types of energy that need to be considered when prioritising the environmental impact of a build, and sometimes the two are at odds with each other which makes decision making difficult. Operational energy is the energy required to run the home once it’s built – heating and cooling, appliances, etc. Embodied energy is the amount of energy that has gone into the production of the materials and the construction of the house.

We’ve had to make several decisions in which we’ve been forced to prioritise one over the other, and factors such as cost and accessibility influence the final outcome. The first key instance of this was in choosing the foundation type – slab on ground versus raised piers. The slab on ground has much higher embodied energy due to the high carbon emissions of cement, as well as the earthworks required to provide a flat pad. However, the thermal mass of the floor in conjunction with our passive solar design will almost eliminate our heating needs over the life of the house. In addition, we chose slab on ground for improved accessibility (i.e. remove the needs for steps) in order to age in place. The engineers wouldn’t let us have an earthen floor on natural ground without a slab, so we’re minimising the environmental impact by using Cupolex void formers rather than polystyrene to reduce the quantity of concrete used.

Building design

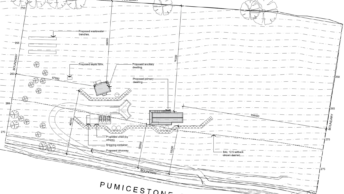

We’re actually going to be building two dwellings at the same time – a house and a cottage. We’ve kept the designs as simple as possible, to reduce costs and ease construction. Both designs have prioritised consideration of environmental impact, accessibility, affordability, and ease of construction.

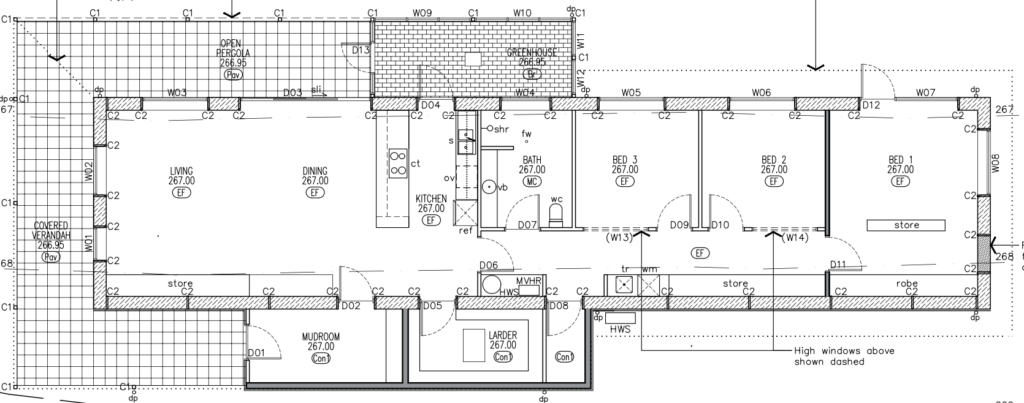

House

The house has three bedrooms and one bathroom, with an additional composting toilet. On the southside is the mudroom entry and a generous sized larder with an earth cooling tube. There is an attached greenhouse on the northside which will be directly accessible from the kitchen, and the shower will have a view into the greenhouse. An open pergola on the northside of the living area will grow grapevines to provide seasonal shading. A verandah wraps around the west and south to eliminate western sun and provide a covered entry point.

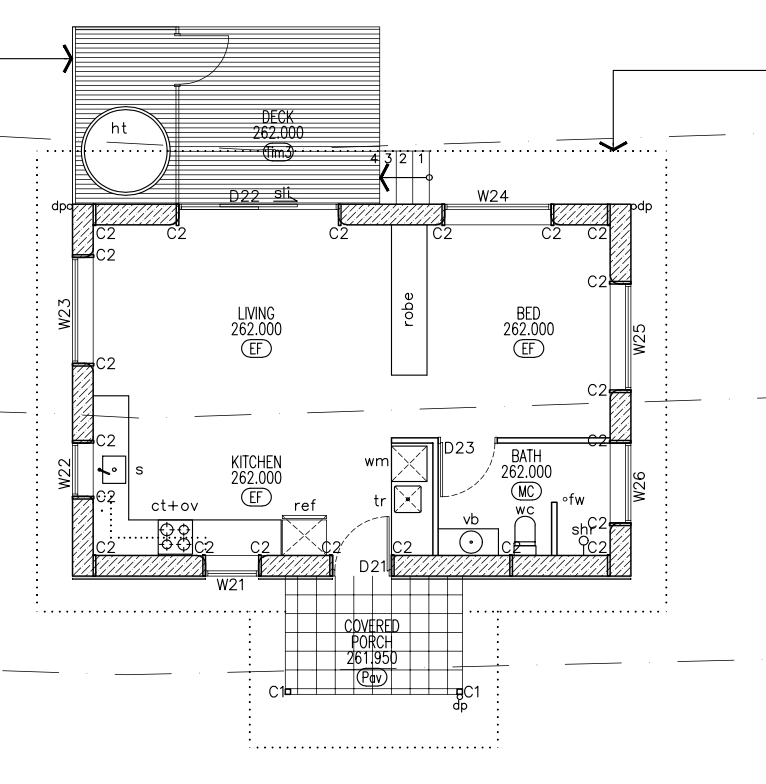

Cottage

The cottage will be a place for family and friends to stay, and we also intend to host farm-stay style experiences. Like the house, it’s also designed for passive solar gain, and the north-facing deck has a sunken wood-fired hot tub. To reduce costs and ease construction the cottage is designed with the same materials as the house – it’ll be a mini version of it!

Assuming we don’t have any further major delays, we’re hoping to be laying a slab this October. We can’t wait to get our hands dirty and see our paperwork become reality.